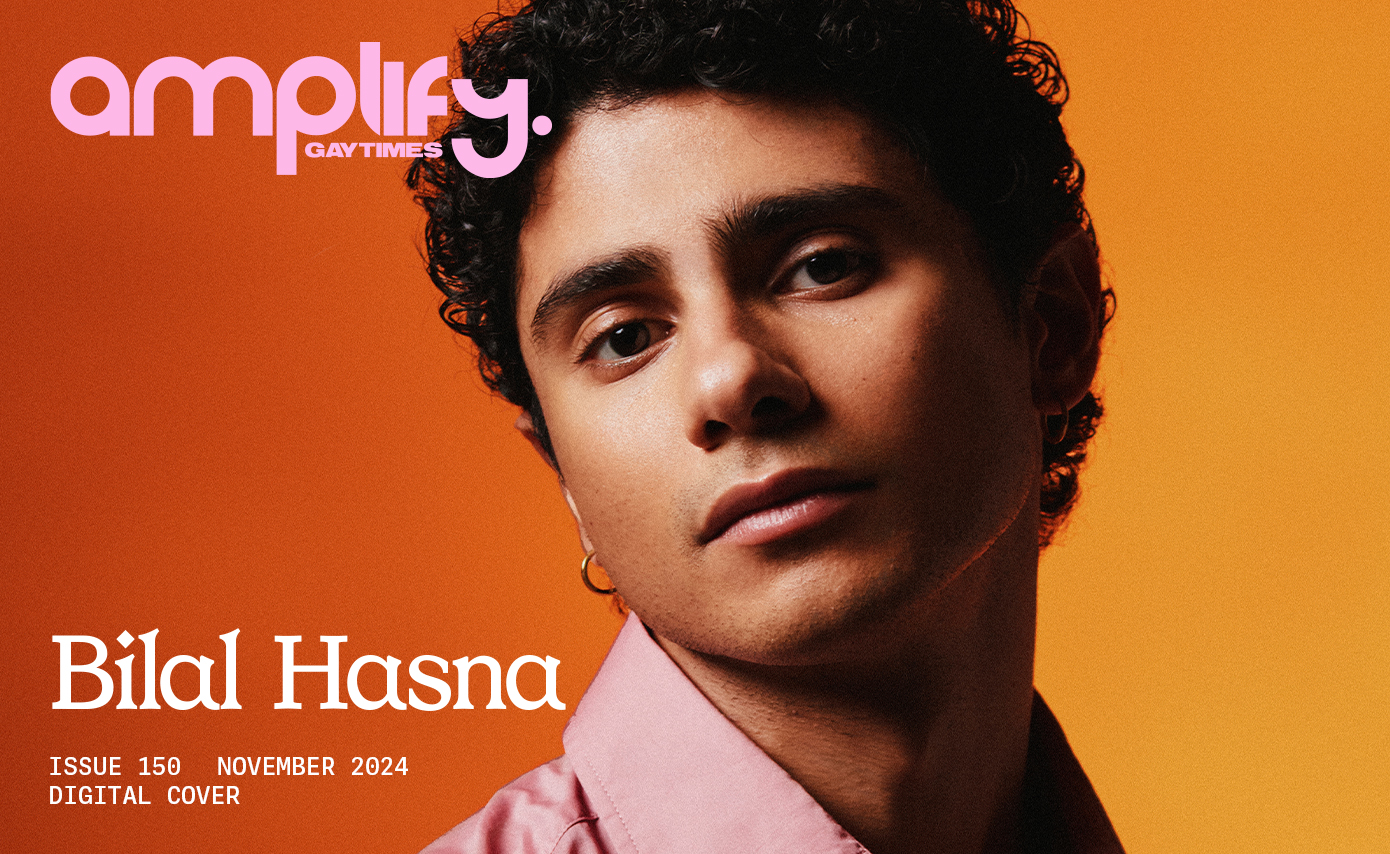

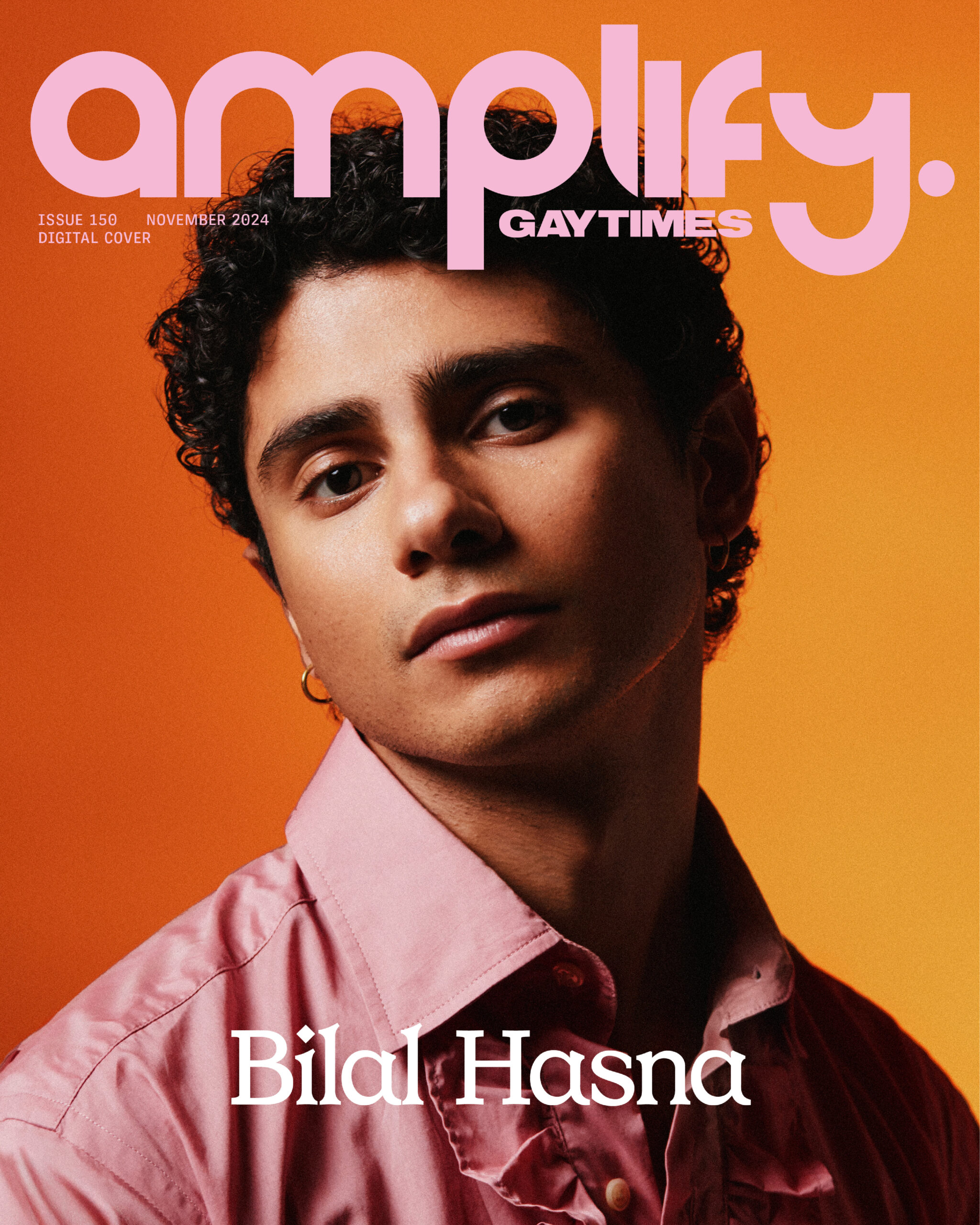

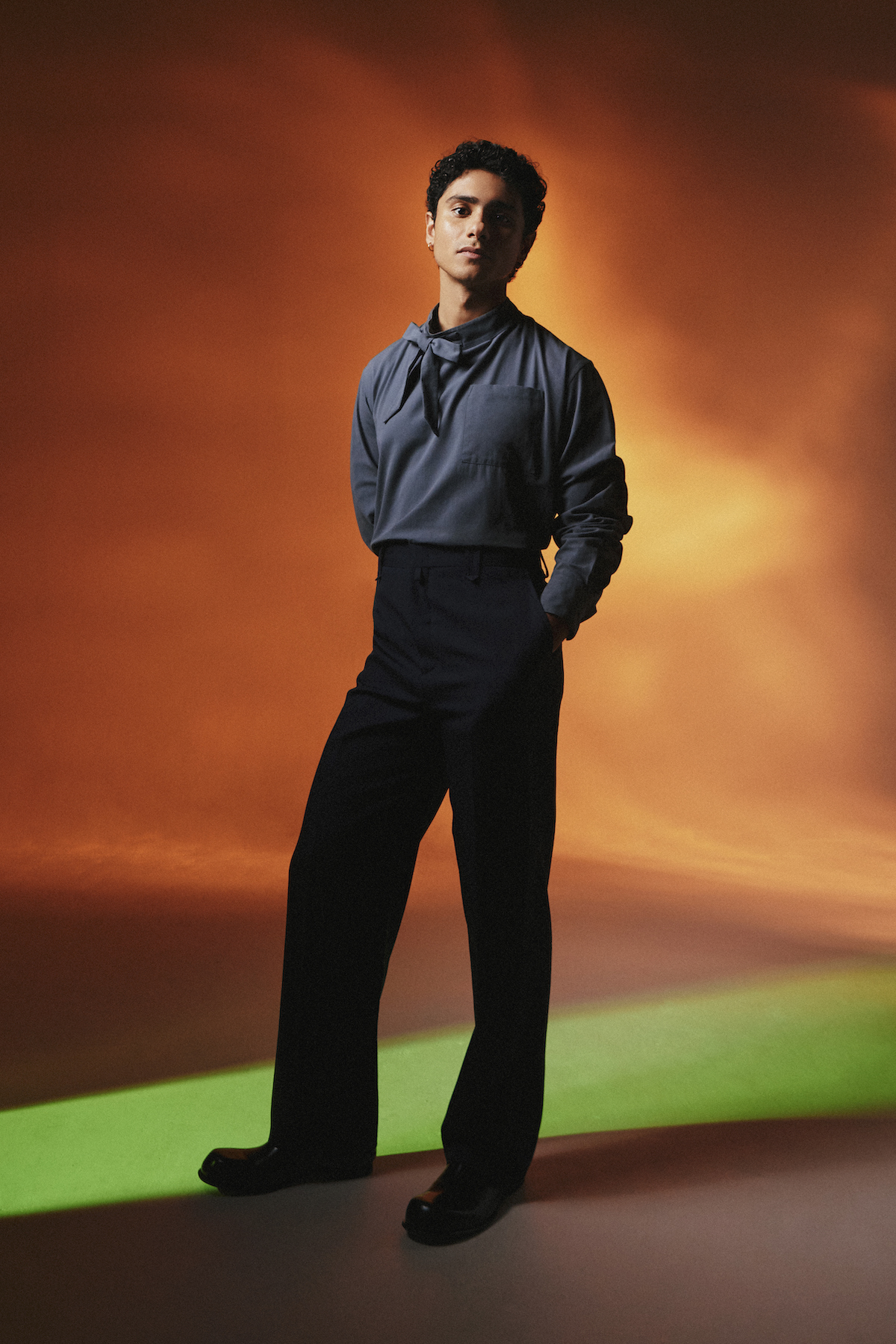

WRITER RYAN CAHILL PHOTOGRAPHER KYLE GALVIN STYLIST OLIVER FRANCIS CREATIVE DIRECTION CRAIG HEMMING GROOMING NICK ROSE PHOTOGRAPHY ASSISTANT GARY SALTER TAILORING FRANKIE FARMER PRODUCTION ANGEL B PRODUCTIONS

Actor Bilal Hasna on his latest role as a non-binary British-Palestinian drag queen in the brilliant Layla.

Actor Bilal Hasna has been incredibly hard to pin down. In the midst of press tours, auditions and a packed shooting schedule, we finally manage to find a time to chat over Zoom. As he flashes on screen, his first instinct is to apologise profusely at being unable to meet in person, telling me that he’d just come from an audition and would later be attending an event for the launch of The Agency, a new show in which he stars alongside Michael Fassbender, Richard Gere and Jodie-Turner Smith. He’s instantly disarming, charming and well-spoken – even taking a moment to compliment my Le Cruset butter dish (not sponsored!) in the back of the shot.

Hasna’s big break came when he was cast in Extraordinary, the anti-superhero comedy series on Disney+ in which he plays Kash, a young man in his early 20s who possesses the power to turn back time. In the role, Hasna showed us that he was ideally suited to comedy, with brilliant timing and line delivery which perfectly suited the world created by Emma Moran. Despite two brilliant seasons, the future of Extraordinary remains uncertain with no news of a renewal – but it played its part in putting Hasna on the map.

His latest role, though, will allow viewers to see a different side of him. Starring as the title character in Layla, a new film written and directed by British-Iraqi filmmaker and writer Amrou Al-Kadhi, Hasna transforms into a jobbing drag queen who starts a relationship with a corporate marketeer. The story unravels as Layla hides their true identity from their family and navigates a double life alongside romance and friendship. In the role, Hasna is mesmerising. He perfectly captures the internal struggle of code-switching between the straight and queer worlds, whilst offering a sense of hopefulness and quiet optimism which sets Layla aside from so many other queer characters that we see on-screen. It’s a nuanced and bold performance, packed with perfect portrayals of love, heartbreak, identity crisis, managing family and friendships and navigating London life.

After receiving acclaim following its premiere at the London BFI Flare Festival, the film is officially released on Friday 22 November. Ahead of the release, we caught up with Hasna to discuss his appreciation for drag, the tragedy trope in queer media and his Palestinian heritage.

To start with, I wonder if there’s a performance or moment in a film that made you realise that you want to be an actor?

I remember that when I was really young, my New Year’s resolution was to watch a film every day. My Dad is a massive film buff so we would watch them together. I remember we watched Girl, Interrupted and Angelina Jolie’s performance in that was so good. I couldn’t stop thinking about it for ages. I just remember being really struck by that performance and I couldn’t stop thinking about it for weeks and weeks afterwards. That definitely was something that inspired me to pursue acting.

And from there, what was your pathway into the industry?

I’ve always done it, since I was a kid. I used to go to a Saturday school like Stage Coach, and then when I went to secondary school, I did a lot of it there. I was really lucky because the drama department in my school had some amazing teachers. One of them was a woman called Dawn Morris-Wolffe and she was directing a production of Great Expectations, the Charles Dickens novel. She wanted a boy to play Miss Havisham and I ended up getting the part. That was my first proper experience of doing drag! She’s a widow, she lives in this rotten house. She’s very camp! A lot of the teachers that came to watch were like ‘Oh my god, I didn’t realise it was you! I thought it was a woman’. It felt really liberating. It really unlocked things for me. Funnily enough, I got a text from her last week saying ‘I’ve just seen the trailer for Layla, I can’t believe it. I hope you’re telling the world about Miss Havisham!’ Then when it got to GCSEs I decided to take more of an academic approach. I ended up going to Cambridge as I wanted to be a professor of English Literature. Weirdly, there was another play that was at uni and I just got the bug again. I got to go around Europe touring Othello, I got to go to the Edinburgh Fringe two years in a row. I got an agent from uni and slowly things started happening.

Tell me about the moment of being cast in Extraordinary.

Extraordinary was the first big break really! I worked for a charity for a year and that was amazing and then I did this prison drama called Screw. I had enough money to support myself so I was able to put more effort into self-tapes and auditions. Then, the Extraordinary tape came through and I got it. That was incredible. Within three weeks of the final audition, I was on set all the time as one of the main characters. With that comes a lot of pressure, but I think I’ve just been lucky enough to work with all the right people at the right times. I really feel so blessed.

Let’s chat about Layla. I’ve seen it twice. I found it to be a very complex watch in the best way. I definitely saw aspects of my own journey. Tell me a bit about how it came to you.

I was aware of Amrou [Al-Kadhi’s] work because they’re quite a prominent British-Arab queer writer in London, and there aren’t that many. I remember listening to a podcast they did for BBC Sounds, and I was in my second year of university and it really made me think differently about my identity. Then, three years later, the self-tape came through for Layla, their directorial debut. I was like ‘I’ve got to try and do that.’ I remember I was actually on the plane to go to Palestine to visit my family, and I did the self-tape in Palestine in the West Bank.

What were your thoughts on the script?

It felt very nuanced. I think so often in queer stories there is this centering around trauma and external conflict that is often quite violent and harsh. I think what happens in Layla is a lot about what people aren’t saying. It’s about what people cannot say, it’s about what people think they shouldn’t say. It’s all about miscommunication, really. I just felt very true to my experiences and it felt very, very authentic. This idea of code switching, depending on what room you’re in, what you feel, the perceived expectations of who you are is also something I could really identify with.

Also, rather selfishly, I just wanted to try my hand at drag!

“So often, queer films show us that queer life is impossible and that you’re going to have to live a miserable life, be depressed or die, basically. I think Layla really rallies against that. It rallies against fatalism.”

What was Amrou Al-Kadhi like to work with as a director?

Amrou [Al-Kadhi] was incredibly passionate about telling this story. I think initially the script was much more semi-autobiographical than it is now. I think they would feel confident with me saying that this didn’t necessarily happen to them but it’s based on experiences that have been refracted through certain lenses. I think because it’s rooted in a lived experience, it meant that they had such an incredible passion and worked so hard to realise this world, both on screen and off. Many of the heads of department were queer, the person who was to apply my makeup was a drag queen themselves! That kind of spirit of authenticity, joy and integrity really ran through the whole team and was led by Amrou.

I feel like it’s cliche to say that playing this role was ‘brave’, but you expose yourself both physically and emotionally in Layla. I imagine that was quite a huge undertaking. Did that come with any kind of pressure?

At that point I’d only really played Kash in Extraordinary and that’s a very comic role. There’s not that much vulnerability required in the way that it is in Layla. I don’t think I felt pressure really, and I think it’s in large part down to Louis [Greatorex] and how much we were able to hold each other in the filming process. I never felt like I was putting myself out there or doing something that I felt uncomfortable with. We also had an intimacy coordinator so that made us feel extremely comfortable. I think because the film was made by our community, you’re always held in it.

I always find that when we’re seeing those intimate scenes in queer media, they’re either depicted to satisfy the heteronormative gaze, or, on the opposite end of the spectrum, they serve the purpose of titillation for the queer viewer. However in Layla, they felt intimate in a way that was necessary for the story, but also really honest to queer intimacy. They felt more genuine than what we’re used to seeing in queer media.

That was definitely our intention. There’s three main sex scenes in the film and I think that they’re quite pivotal for the film because they express what these characters can’t quite tell themselves verbally.

Has playing Layla given you a whole new appreciation of drag?

Yes! Drag is an Olympic sport. Drag queens are Olympians! To be in a corset that cinches you five inches and nine inch stilettos, even for a few hours, is exhausting! To hold everyone’s gaze and to translate their investment in your persona into something that is righteous, clever and quick requires so much! I’ve always loved drag, but I think doing this film really made me understand the lengths that you have to go to to be a professional drag queen.

What do you hope that people will take away from the film?

I hope the film shows them that life is possible. I think so often queer films show us that queer life is impossible and that you’re going to have to live a miserable life, be depressed or die, basically. I think Layla really rallies against that. It rallies against fatalism. Layla, by the end of the film, emerges triumphant and as someone who’s able to harness all the different facets of themselves into something beautiful and coherent. I really hope that is the case, especially for queer Arabs and queer Muslims whose identities are so often recognised in mass media to justify atrocities.

You’re right, a lot of queer media is rooted in tragedy. Why do you think that is?

I think that in the context of queer filmmakers and queer showrunners, a lot of people are trying to portray the truth of their experience and that truth is often quite tragic. You don’t even need to look to the past, you can look at the present. For example, right now we have rampant transphobia. It’s very easy to tell a queer story that’s traumatic because for so many people, queer life is something traumatic. We’ve all had trauma associated with our identities. I think the problem is that there’s an over-saturation of those stories, which means that you begin to naturalise certain things around queer life. If you’re just reflecting your own experiences without trying to show that another world is possible, then the imagination will never be able to grasp it, and therefore you can never realise it. I’m a big believer that the imagination is actually quite a political tool. You cannot achieve anything unless you can envisage a world in which it is possible.

Speaking of politics, I see from your Instagram that you’re regularly sharing political posts. Do you feel that you have a responsibility to utilise your platform in that way?

As a Palestinian actor, it’s particularly painful for me to see what’s going on in the world right now. Today, as we speak, is the 404th day of a genocide against the Palestinian people in Gaza. I think that I feel a sense of duty that is incumbent on me to speak out about it because I don’t think any of us have seen anything like this in our lifetimes. Do I think it’s my responsibility? The act of storytelling goes hand-in-hand with the act of advocacy and uplifting people whose voices are lost in public discourse, whose voices are demonised, dehumanised, racialised. I see the act of advocacy and lifting up certain stories as something I want to do on screen, as well as off. Especially with this issue, it’s particularly important because there is such fear around talking about it. There is such fear in saying the wrong thing. I take a great sense of hope in the people that have refused for their humanity to be compromised in this moment and have taken to the streets or have used whatever platforms they have to draw attention to this. You described it as a political thing, which is true. The situation is a political situation, but the actual issue itself is really an issue of: do we believe a certain kind of person should be annihilated? I think the answer to that is always no.

Thank you for answering that question so eloquently.

With regards to this specific issue of Israel-Palestine, in my opinion, for many years now the Israeli state has weaponised queer Palestinian identity in order to justify its occupation of Palestine. So essentially it’s said that because homosexuality is not accepted, in Palestine, that this is actually a reason why the Palestinians need to be occupied because they are backwards people, because they don’t understand true liberation. They don’t stand for LGBTQIA+ rights. I think what this film is trying to do, in a small way, is saying that we have to narrate our own stories, because if you ask any queer Palestinian, the first thing they will tell you is that nothing kills queer Palestinians more than Israeli bombs.

That brings me onto my next question, which is about identity. Typically when we see queer films or TV shows, they’re usually from a white gay male perspective, and there’s a greater need for wider representation. What are your thoughts on that?

I think that in queer representation, as in any form of representation, a certain kind of person is prioritised over other people’s perspective. I really hope that that’s beginning to change. Layla sits alongside many films about drag queens of colour that have come out in the last few years, and I think that’s a really good starting point. It’s hard to say what the future is going to look like, but I do feel very hopeful about all different kinds of queer experiences being shown.

Can you give us a little snapshot of what you have coming up?

I think this year has been really exciting. I’ve had a real opportunity to work with such a diverse range of people, a lot of whom I’ve been working in this industry for a long time. I’ve just wrapped on this show called The Agency, which is for Showtime and Paramount+. It’s written by Jez Butterworth and John-Henry Butterworth. The first episodes have been directed by Joe Wright, the amazing director of Pride and Prejudice, Atonement and The Darkest Hour. The show stars Michael Fassbender, Richard Gere and Geoffrey Wright. So that was a crazy opportunity to act with some of the big veterans of Hollywood, and it was amazing.

I learned so much. That comes out on 29 of November. And then I actually had the opportunity of being in the Lord of the Rings anime film that’s coming out. There’s also Black Mirror, which is amazing as well. I can’t say too much about that, but that’s coming out next year!

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Layla is out in UK cinemas on 22 November.

The post Bilal Hasna: “Drag is an Olympic sport. Drag queens are Olympians!” appeared first on GAY TIMES.

0 Comments