The Finnish designer and creative director’s sensual, subversive garments empower butch bodies in the now, while their HÄN Archive project celebrates non-binary, trans, gender non-conforming and lesbian folks from the past.

WORDS BY JAMIE WINDUST

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JODY EVANS

MODELS: BAMBIE JORDAN PHILLIPS, DANNIE SPOONER, GII

Welcome to Queer by Design, a new monthly column by GAY TIMES Contributing Editor Jamie Windust. Here, Jamie profiles emerging designers about the intersections of style, identity and expression and how these factors inform their creative practice.

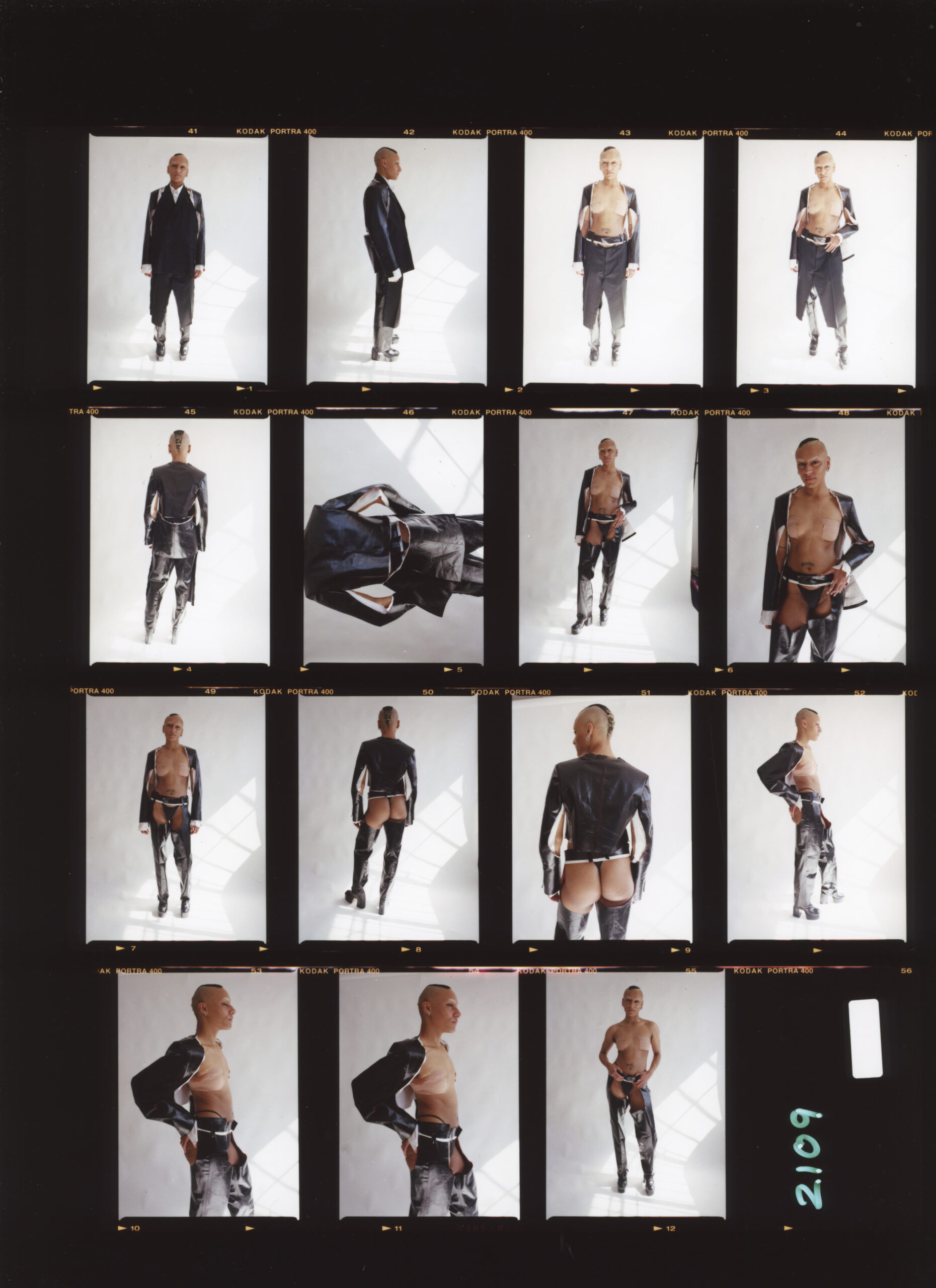

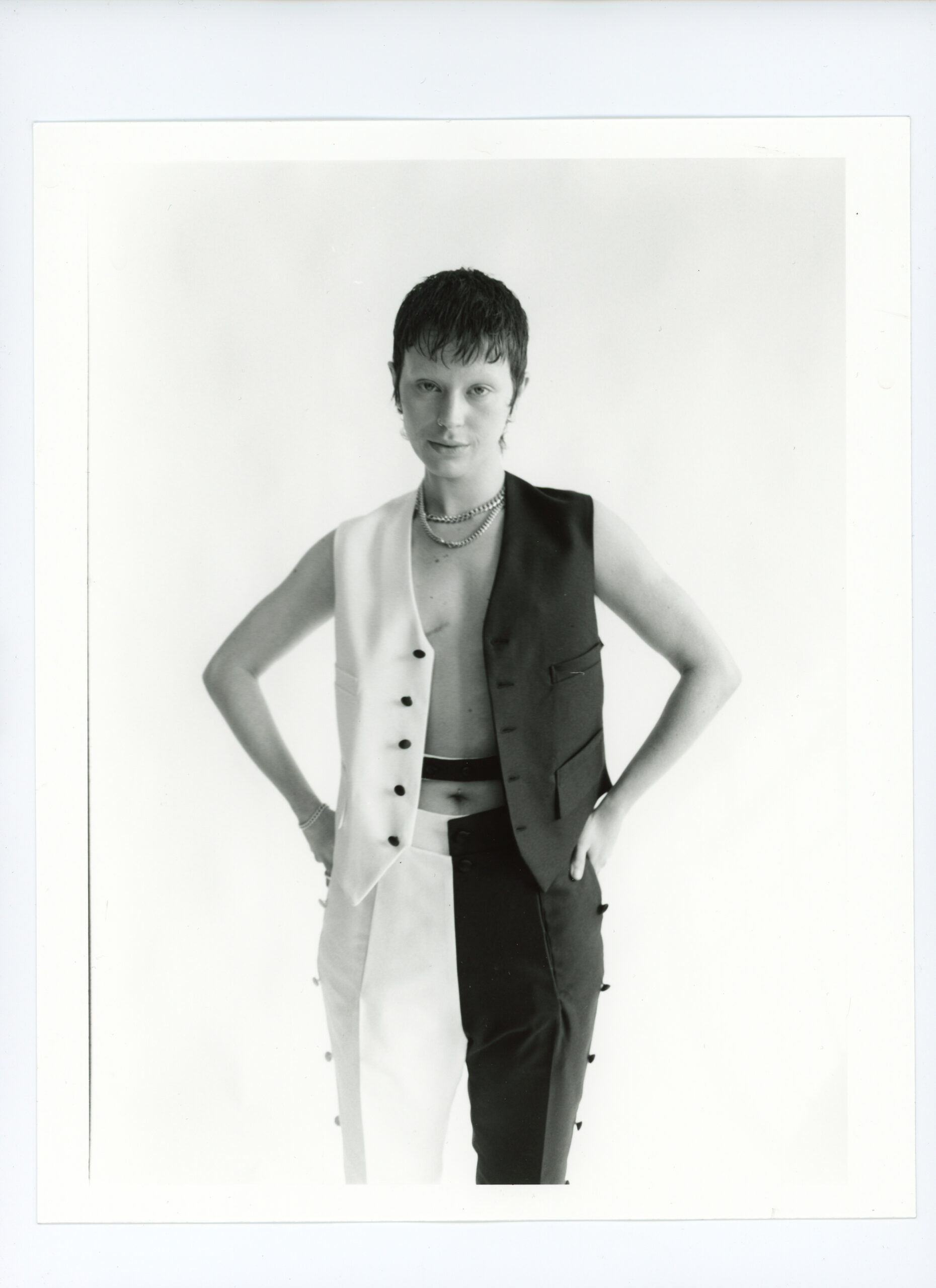

Transcending the lines between fashion and art, designer and creative director Ella Boucht’s subversively sexy tailoring is centred on empowering butch, trans and gender non-conforming folk through clothing.

A graduate of both CSM grad and the Swedish School of Textiles, Boucht spent their student years sifting queer archives but was struck by the lack of representation of the communities around which their work now centres. As a result, they turned to influencers like dyke photographer Lola Flash and 1920s gender-non-conforming boat racer Joe Carstairs – figures who don’t just inform Boucht’s aesthetic but their ethos and values.

Promoting queer body confidence and promoting butch eroticism, Boucht uses upcycled fabrics to subvert and queer workwear with ties emblazoned with logos like DADDY IS A DYKE and leather waistcoats which seem to reference London’s kinky Rebel Dyke past. These garments aren’t just unapologetic – they question why we should ever apologise for queer expression in the first place.

Now, as creative director for HÄN Archive – a digital space dedicated to preserving non-binary, trans, GNC and dyke stories over the decades – Boucht isn’t just centring queer history in their work, they’re making it, too.

GAY TIMES spoke with Boucht about their mission to broaden the established narratives of queer history and helping dyke, GNC, trans+ and non-binary communities feel “body euphoric” in tailored designs.

What initially drew you to fashion as a creative outlet? Did you feel there was a sense of community and safety there for you as a queer person?

It was actually through my desire to become an actor that I got drawn into fashion, or more so the craft of sewing, cutting and tailoring – especially after experiencing the wardrobes at my theatre school and at the National Opera and Ballet in Helsinki. I wanted to learn all aspects of creating a garment, which eventually led me towards design and fashion. They have become tools for me to express myself, my creativity and understanding of the world.

The connection to queerness in my creative practice only developed during my MA at CSM. Arriving in London’s queer community was when I felt empowered to use and express my own experiences as a queer person in my work and collection narratives. I wouldn’t say fashion as an industry gave me the sense of community or safety. It was more London and the people I met here outside of the industry. Fashion is a very fast-paced, opportunity-driven, transactional and extractive industry – as, arguably, many others are – which feels rather hostile to the spirit of community, queerness and a sense of safety.

Instead, I’d say that the many collaborative projects and my practice of bespoke tailoring and hear work enabled me to connect with fellow queers more intimately – and developed a space of visibility and play where I felt I could create freely with people and through our queerness.

When you first began looking into the archives of queer, trans and non-binary folk in fashion, what was your initial reaction to what you saw?

The first time I started exploring queer archives and history, I realised how much dyke, lesbian, trans+ and non-binary legacy, culture and photography was either hidden in private archives or in the basements of book shops, deep in the corner of a library or worst case completely censored or destroyed, making it harder to access. This recognition generated a deep commitment in me to make archival materials and ongoing experiences of dyke, trans+ and non-binary identities more accessible and visible through my work.

Within my queer fashion research, what I mostly came across was the representation and visibility of cis, gay men. They were on the front covers, head designers, creative directors and often leading voices, whilst finding lesbian, dyke and/or trans+ representation was rare if coming across any at all. What in the end influenced my work the most was the rich lesbian, dyke, trans+ and genderqueer voices outside of fashion – coming across people like Jack Halberstam, Lola Flash, Phyllis Christopher, Joe Carstairs, the people behind [lesbian erotica magazine] On Our Backs and more. Their rich history, erotic power, sense of style and unapologetic expressions gave me hope and laid the foundation to my creative values and aesthetics today.

By grounding my creative practice, tailoring and leather work in those archival materials and the rich creative work and representation of dyke and trans+ people today, I strive to expand the boundaries of queerness, gender and sexual expression in fashion.

What has the response been like to your designs from trans/non-binary folk?

It has been incredible, and very humbling to receive so much love and appreciation for the work from the community. This goes for both, the people I’ve worked with as well as strangers, coming across my work online or at exhibitions and sending the occasional private messages loaded with enthusiasm. These encounters are an affirmation to why I am doing this work, they have given me a lot of inspiration and drive to keep going.

Aside from verbal feedback, seeing trans+ and non-binary customers getting dressed in their bespoke or made-to-measure garments for the first time and witnessing their reactions is probably the most rewarding gift that I, as the designer and tailor, could ever receive – the smile, confidence and joy is invaluable.

Working with trans+ and queer people has also led me to offer creative alterations which I’m incorporating more and more into my work. It allows people to bring their cherished garments to be tailored to their own measurements, redesigned to fit their body type and be aligned with their gender identity. It’s also a way for me to offer more affordable solutions and invite a wider audience into my work. Living and working in London as a designer and tailor comes at its costs and this simple reality can make my work inaccessible to a lot of people I’d hope to cater to.

Would you say your work is healing in a way?

Yes, I would say it’s a very healing and transformative process; using bespoke processes to create clothing that fits your body and gender identity no matter who you are can be a very healing experience, feeling body euphoric. Speaking for myself and my own gender experience with clothing, it really makes a difference to find a garment that feels like it has been designed with your body in mind. My work is a space for me to reflect on my own gender exploration and what it means to navigate through a largely heteronormative and patriarchal world as a trans+ non-binary person. It leads me to challenge norms, what we think we already know, and resolving or answering a question/topic from a queer lens which I translate into garments, methods and systems for queer fashion. An example could be how we can create trans+ inclusive pattern cutting for the industry and break the binary of menswear versus womenswear.

What do you hope archivists in 100 years time find when they look back on queer fashion now?

I hope that [archivists] will look back to our century and see this as a pivotal time of genuine queer and trans-liberation, celebrating a strong culture of freedom of expression and seeing actual systems change. I’d love for them to see a fashion industry that embraced queerness beyond performativity, Instagram likes and popularity in mind but that employed queer politics from within to move towards more equitable, sustainable and healthy practices.

It not only matters who’s on the runway, but we need to see queer, trans+, non-binary people, dykes and lesbians – and anyone else with experiences of marginalisation – taking on roles as creative directors, leadership positions and being more represented within the industry’s professions overall.

Follow Ella Boucht here and find out more about the HÄN Archive here

The post Across timelines, Ella Boucht is helping dykes and trans+ folk take up more space appeared first on GAY TIMES.

0 Comments